The archivists' decision, based on guidance provided by Bill Clinton that restricts the disclosure of advice he received from aides, prevents public scrutiny of documents that would shed light on how he decided which pardons to approve from among hundreds of requests.

Clinton's legal agent declined the option of reviewing and releasing the documents that were withheld, said the archivists, who work for the federal government, not the Clintons.

The decision to withhold the records could provide fodder for critics who say that the former president and his wife, Sen. Hillary Rodham Clinton, now seeking the Democratic presidential nomination, have been unwilling to fully release documents to public scrutiny.

Officials with the presidential campaign of Sen. Barack Obama, D-Ill., criticized Hillary Clinton this week for not doing more to see that records from her husband's administration are made public. "She's been reluctant to disclose information," Obama's chief strategist, David Axelrod, told reporters in a conference call in which he specifically cited the slow release records from the Clinton library. "If she's not willing to be open with (voters) on these issues now, why would she be open as president?"

In January 2006, USA TODAY requested documents about the pardons under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). The library made 4,000 pages available this week. However, 1,500 pages were either partially redacted or withheld entirely, including 300 pages covering internal White House communications on pardon decisions, such as memos to and from the president, and reports on which pardon requests the Justice Department opposed.

In a statement, the Clinton campaign said that "all of the redactions made to the pardon-related documents were made by (the National Archives)."

Former president Clinton issued 140 pardons on his last day in office, including several to controversial figures, such as commodities trader Rich, then a fugitive on tax evasion charges. Rich's ex-wife, Denise, contributed $2,000 in 1999 to Hillary Clinton's Senate campaign; $5,000 to a related political action committee; and $450,000 to a fund set up to build the Clinton library.

The president also pardoned two men who each paid Sen. Clinton's brother, Hugh Rodham, about $200,000 to lobby the White House for pardons — one for a drug conviction and one for mail fraud and perjury convictions, according to a 2002 report by the House committee on government reform. After the payments came to light, Bill Clinton issued a statement: "Neither Hillary nor I had any knowledge of such payments," the report said.

The pardon records released by the library divulge little that might settle debate about those and other pardons. But they do shed new light on the volume of clemency requests that former president Clinton received — and the pressures he and his staff faced as friends, advisers, political leaders and foreign heads of state weighed in to influence which petitions would be granted.

The files contain handwritten letters from several of the president's close associates. Former Democratic Party chairman Donald Fowler of South Carolina wrote a note seeking clemency for former congressman John Jenrette, D-S.C., who was convicted in the 1980 Abscam sting in which FBI agents, posing as Middle Eastern businessmen, offered lawmakers bribes for political favors. Clinton did not grant the pardon.

Most of the withheld documents, including dozens of clemency pleas sent to the president, were blocked from release under FOIA rules that protect personal privacy. The 300 pages of internal White House documents on pardon requests were blocked under the Presidential Records Act of 1978, which allows presidents to maintain the confidentiality of communications with their advisers for up to 12 years after they leave office.

In 2002, Clinton sent a guidance letter to his library that urged quick release of most White House records but retained the confidentiality prerogative covering advice from his staff. Still, Clinton said the restriction should be interpreted "narrowly" and allowed that certain records detailing internal communications could be made public if reviewed and approved for release by his designated legal agent.

Emily Robison, the library's deputy director, said Clinton's agent, former deputy White House counsel Bruce Lindsey, chose not to review the withheld documents.

Lindsey "was given the opportunity to look at what we withheld under the (president's) guidelines, and he chose not to. … Only Mr. Lindsey and the president have the authority to open those," she said.

The William J. Clinton Foundation, which Lindsey helps oversee, said in a written statement that the National Archives is responsible for deciding which records are withheld under the Presidential Records Act. Archivists were exclusively responsible for "determinations with respect to these materials," the statement said.

Clinton's guidance to the library goes beyond his predecessors, George H.W. Bush and Ronald Reagan, in urging that most of his presidential records be released quickly, according to Tom Blanton of the National Security Archive, a research institute at George Washington University that collects government records for public use.

Blanton noted that Lindsey's refusal to review the withheld documents could be viewed as an effort to ensure the archivists' independence. "He's saying the professional archivists get to make this determination; it's not a political determination."

The archivists' decision to withhold records that could be construed as confidential communications between Clinton and his advisers is more consistent with the Bush administration's hard line on the release of White House records, Blanton said.

President Bush signed an order in November 2001 that broadened former presidents' prerogative to block the release of internal White House records. That order, which Bill Clinton opposed, also allows a president's immediate family to assert the privilege.

In 2004, Judicial Watch, a conservative public interest group, went to court to force the Bush administration to release Justice Department records on Clinton's pardons, and a federal judge ordered that the records be opened. But the administration, which argued that such releases would undermine a president's ability to get confidential advice, blacked out most of the documents it made public.

Christopher Farrell, a Judicial Watch director, noted that the pardon records blocked by the library also included all Justice Department reports that were sent to Clinton with recommendations on which clemency requests he should deny. He said it was "ridiculous" to withhold clemency petitions over privacy concerns. "These are people who were convicted in a court, and those cases are a matter of public record."

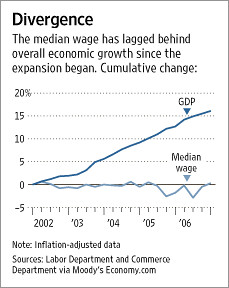

I never tire of posting this graph of the "W economy", because it summarizes in a nutshell what happened: growth happened, but was not shared widely. Thanks to wage stagnation, made possible by the threats of outsourcing and offshorization, and by consistent policies over the last 30 years to deregulate and liberalise markets, starting with labor markets), the fruits of growth have to a large extent been captured by a very few - but this has been hidden because consumption was propped up by readily available debt and the apparently growing virtual wealth of homeowners.

I never tire of posting this graph of the "W economy", because it summarizes in a nutshell what happened: growth happened, but was not shared widely. Thanks to wage stagnation, made possible by the threats of outsourcing and offshorization, and by consistent policies over the last 30 years to deregulate and liberalise markets, starting with labor markets), the fruits of growth have to a large extent been captured by a very few - but this has been hidden because consumption was propped up by readily available debt and the apparently growing virtual wealth of homeowners.