This is so to the point, so penetratingly wise, I'm copying the whole thing.

Yes, it's long.

The market mindfuck

By The Scanner

“I believe that America's free market has been the engine of America's great progress. It's created a prosperity that is the envy of the world. It's led to a standard of living unmatched in history. And it has provided great rewards to the innovators and risk-takers who have made America a beacon for science, and technology, and discovery…We are all in this together. From CEOs to shareholders, from financiers to factory workers, we all have a stake in each other's success because the more Americans prosper, the more America prospers.”

— Barack Obama, New York, NY, September 17, 2007

Mark Thoma is an economics professor who runs the informative blog Economist’s View. Politically, he’s your standard-issue Democrat and he recently treated us to a standard-issue vision of economics as seen by Democrats:

This article by David Leonhardt describes Barack Obama's view of economic policy, and it is very similar to my own. Most of the time, it is best to leave markets alone, to let them work without intervention, and that should be our starting point. But markets fail, and part of the disagreement with those holding more conservative views is over how often markets fail, whether they can easily self-correct when there are problems, and how effective the government is at fixing problems when they exist.

Thoma is a victim of what is clinically termed the market mindfuck – a malady believed to affect over 90% of Democratic politicians. Now, in his academic work, Professor Thoma is a specialist in monetary economics and Fed policy, and it’s fair to say that like most elected Democrats he’s an admirer of the institution in general (and of Ben Bernanke’s policies in particular). So to provide some context for the market mindfuck, let’s briefly review what the Fed does.

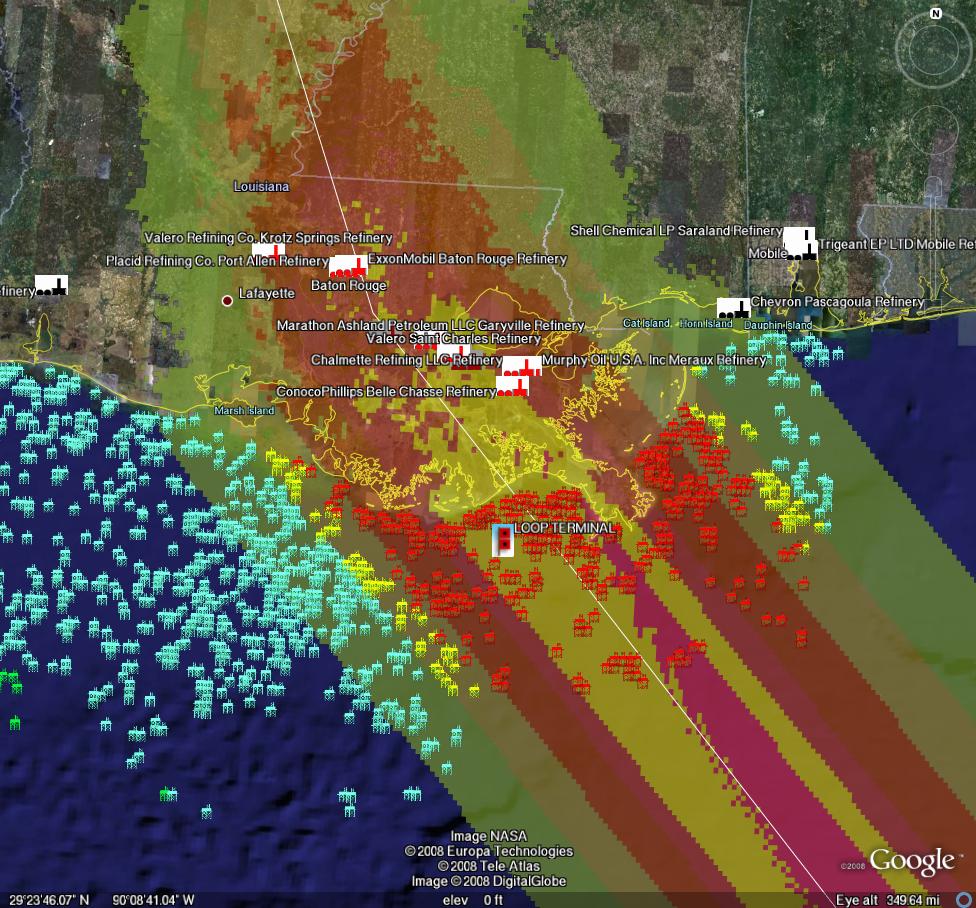

Pursuant to the 1913 Federal Reserve Act and subsequent amendments, the government is effectively given an absolute monopoly on private bank reserves. A committee of government planning bureaucrats in Washington, known as the F.O.M.C., dictates the nationwide price of these reserves and feeds instructions to a bureaucratic department in New York. Based on these instructions, the department carries out constant intervention in the market -- literally on a minute-by-minute, hour-by-hour basis -- to control the quantity of bank reserves and ensure that the government-mandated price target is enforced at all times.

How do the government planners know what price to set? Being technically skilled state functionaries, they have developed a complex analytical apparatus that allows them to engineer just the right the price. It involves such things as calculating “output-gap estimates,” constructing “modified Taylor rules” and compiling “physical-input material balances” (whoops! sorry, that last one was Gosplan).

The health of the entire economy depends on this process. If the planning intelligentsia does its job well, the nation will be prosperous, demonstrating once again – to the mindfucked – that “most of the time it is best to leave markets alone” and “let them work without intervention” (though there is room to debate “how often” we will be forced, reluctantly, to permit exceptions to the golden rule).

* * *

The market mindfuck thus reveals itself as a formidable tool of ideological control. In accordance with the ancient principle of heads-I-win-tails-you-lose, it works as follows: If you advocate Policy A -- in which the government involves itself in economic decision-making to advance the perceived self-interest of the ruling class -- you will receive the warm approbation of the sages: What a sophisticated proposal; what a pragmatic approach. The Federal Reserve Act, as it happens, was a compromise between a reactionary plutocrat, an apologist for the Belgian rape of the Congo who called the income tax “communistic” (Sen. Nelson Aldrich of Rhode Island), and a bloodthirsty Southern white supremacist for whom no law “is so obnoxious that I would be willing to submit its fate to 146,000 ignorant Negro voters” (Rep. Carter Glass of Virginia).

On the other hand, if you advocate Policy B, in which the government involves itself in economic decision-making to benefit the working class, you will be summoned in grave tones before a tribunal of the very best men, who are charged with the duty of upholding the sacred doctrine – the doctrine that “most of the time, it is best to leave markets alone, to let them work without intervention, and that should be our starting point.”

Swiftly you will see the ideological enforcers – journalists, economists, think tankers, politicians -- gather around you with looks of pity and concern on their faces. Somewhere in the room you will hear the sound of a door being bolted from the inside. Don’t be afraid, they’ll say in soothing tones. You’re among friends here. Believe us, we understand your feelings. But we’re concerned that you’ve lost sight of some fundamental truths. We want to help you, but first we need to hear you say, in your own words, that “most of the time it is best to leave markets alone, to let them work without intervention, and that should be our starting point.” You can say that, can’t you? Just say the words.

You feel the icy stare of the faceless men arrayed against you. With panic rising in your chest, your mind flashes wildly to the New York Fed trading desk where at this very moment the national price of bank reserves is being fixed by people who look exactly like these men. You catch sight of one of your tormentors in a corner of the room, a former IMF official holding a gleaming copy of the Economist with a pair of electrical pliers folded inside. You want to shout no, but gripped by terror you collapse and crumple in your chair. In a slow, mechanical drone, you mouth the words: “It is best to leave markets alone, to let them work without intervention; that should be our starting point.” Your statement is taken down by a clerk and sent off to the Washington Post for filing. Satisfied, the men rise and move toward the door. The IMF staffer gazes at you with a look of benevolent reflection. (“You were thinking of the F.O.M.C., weren’t you?” After a moment’s hesitation, you nod your head and begin to sob. An almost tender smile comes over his face. “You are no metaphysician, Winston,” he says paternally.)

* * *

Consider the New York Times Magazine article by David Leonhardt that Thoma points to. It begins its discussion of Obama’s economic policy by recalling the hoary “battle of the Bobs” of the 1990’s:

On one side was Clinton’s labor secretary and longtime friend, Bob Reich, who argued that the government should invest in roads, bridges, worker training and the like to stimulate the economy and help the middle class. On the other side was Bob Rubin, a former Goldman Sachs executive turned White House aide, who favored reducing the deficit to soothe the bond market, bring down interest rates and get the economy moving again. Clinton cast his lot with Rubin, and to this day the first question about any Democrat’s economic outlook is often where his heart lies -- with Reich or Rubin, the left or the center, the government or the market.

Here is the market mindfuck in all its gruesome fullness. Robert Rubin wanted the government to redirect income from taxpayers to bondholders. Therefore, he was in favor of “the market.” Robert Reich wanted the government to redirect income from bondholders to road-builders. Therefore, he was in favor of “the government.” Have you got the hang of this? Now try your hand at this stumper: In 2001, Alan Greenspan called for reversing the Rubin budget-surplus policy, announcing that we should now cut taxes for the rich – i.e., redistribute income from bondholders back to taxpayers. Okay. Was Alan Greenspan for “the government” or for “the market,” according to David Leonhardt? (No peeking!)

Or let’s take a different variation of the mindfuck, from the same article. Leonhardt says the “best example” of Obama’s embrace of the free market is his climate policy. Obama supports a cap-and-trade system to cut greenhouse-gas emissions. While many Congressional cap-and-trade bills call for giving away allotments of pollution credits to power companies, an option Leonhardt describes as a form of corporate welfare, Obama wants to auction the credits off. This is supposed to result in a more efficient allocation of credits as well as more money for the treasury. By supporting auctions, Leonhardt says, Obama has “moved the debate toward a more pro-market solution.”

Now, I don’t know much more about this debate than I read in the article; if you take at face value the reporter’s explanation of the issue, the auctions plan appears as the better of the two ideas. But the terminology is incoherent: Obama wants the government to invent a new commodity and create a new market that didn’t exist before, tradable pollution credits; maintain a monopoly on the production of the credits; unilaterally determine the aggregate supply of credits; and then forbid companies by law from emitting greenhouse gasses in excess of their holdings of credits. This is the solution that follows from the dictum that the government usually shouldn’t interfere?

Let’s try to follow the logic. The explanation, presumably, is that in the giveaway plan, the government would determine not only the total number of credits but also the initial allocation of credits among companies; whereas in the auction plan, “the market” decides the initial allocation. But wait! What would be the point of having the government decide how credits are to be allocated among companies anyway, except as a corporate giveaway? Only the total number of credits affects the environment, not their distribution. If there were some pressing environmental reason why we would want to control the allocation of credits, then the “pro-market” auction solution would be a total failure; the distribution of credits would end up being determined by the relative economic value of credits to each firm rather than by whatever environmental criteria we were trying to enforce.

Surely it can’t be the mere existence of an auction that makes the plan “pro-market.” (After all, wasn’t it “pro-government” Bob Reich who wanted to auction off Treasury bonds -- i.e., run a deficit -- to build roads that would probably get built through competitive bidding?) The pollution-credit giveaway plan is neither more nor less “pro-market” than the auction plan. In both cases, the government creates the market. It’s just that in one version, the market is apparently created so as to benefit polluters and in the other one it isn’t. It is hard to resist the conclusion that the auction plan is presented as “pro-market” solely because – at least in this presentation – it’s the better of the two plans.

* * *

The market mindfuck is all the more insidious because the victim, usually a hapless Democrat, is complicit in his own mindfucking. By accepting the premise of the mindfuck, the victim automatically places his own views – indeed, precisely those views which distinguish him from his right-wing opponent -- under a cloud of probationary suspicion. This suspicion can only be dispelled after a rigorous examination process in which the judge and jury are the very ideological enforcers who insisted on the slanted premise in the first place. When the verdict arrives, the victim’s ideas may turn out to be lamentably “anti-market” or intelligently “pragmatic.” Such verdicts closely correlate with cui bono.

There is only one cure for the mindfuck: The patient must refuse to recite the catechism. When enjoined by his ideological enforcers, a strictly rejectionist posture must be assumed: “No, I’m sorry. Most of the time the government should not refrain from intervening in the market. The market is not a better allocator of resources than the government. Government policies create markets. That should be our starting point. Once we all agree on that, then we can debate the real question: Who should benefit from those policies, and how?”

Judging from the Obama quote at the head of this post, we may not see a cure in our lifetime.